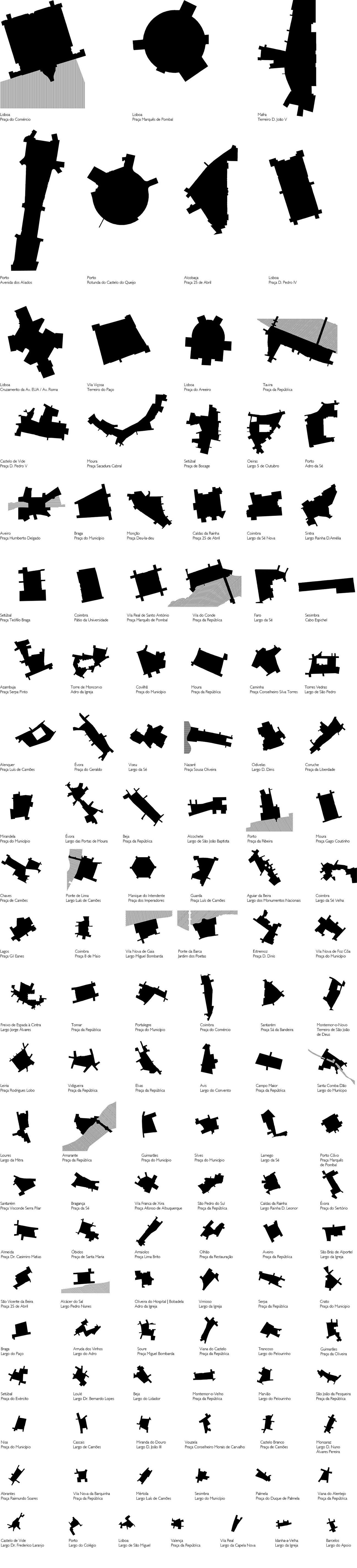

THE SQUARE DIVERSITY

The term praça (square) is Latin in origin - platea – and it is used to identify a public space of an exceptional character that is morphologically distinct from the channel-like spaces that streets make. However, very different spaces correspond to this apparently clear morphology, covered by varied nomenclature and which in some way are not a cultural constant.

Although squares may not exist in certain cultures, in the West they are, by nature, an urban quality prerequisite. This importance dates back to the myth of the Greek agora and Roman forum as spatial supports for civic institutions of which we believe ourselves to be the heirs.

The fact that, in the late Middle-Ages and the Modern Age, the square has served multiple functions – commercial, political, social and religious – bordered by the public and private buildings of greatest importance in the city, has consolidated its collective character and has given it extra importance in comparison with the other urban public spaces. Its hierarchical superiority is evident in any type of fabric, not only due to the functions it supports, but also due to the finite nature of its space, its relative size or quality of its architecture, regardless of the origins behind its shape.

Nowadays, in spite of everything, the traditional square has retained much of its urban role. Although with new outlines, its production as an urban feature after the Modern Movement has seen it linked to what many were already calling “a nostalgic symbol for a lost urban quality”.

Squares in Portugal have naturally gone hand in hand with the country’s urban process: for as long as there have been cities in our country, there have been squares. Therefore it is no coincidence that the origins of cities in Portugal can be largely traced back to Romanisation of the country, both in terms of creating an urban network of new settlements, as well as re-appropriating existing towns and cities. In this way, squares in Portugal exhibit long sedimentary processes, which, although each case is specific, cannot be taken out of the wider context of Western civilisation itself.

Thus, today we find examples of squares that we know originate from Roman fora or even from the ritual spaces of earlier periods. In terms of squares originating from churchyards, there are cases that predate the formation of the nation. The Middle Ages, in particular the later period, left a large number of examples of fairground fields at city gates and spaces connected to religious and military buildings. In most cases, squares serving buildings of important collective value were only defined when these buildings became consolidated. Later, we find examples of this kind of space resulting from the demolition of large buildings, in particular extinguished convents. The 19th century saw designs for squares catering for traffic, which is especially visible in the large roundabouts used, and also gardened urban squares, which in many cases were quite separate from the earlier functions of this type of urban feature. The process was completed in the 20th century by systematic improvements, adding pavements and garden spaces. Contemporary regeneration work ,even when not on a major scale, has nevertheless had an impact on the spaces’ character.

The travails of time that have impacted on the squares as the urban fabrics have evolved are inseparable from the fabrics’ own ups and downs. This is because squares are an integral part of these fabrics – they are one of the main physical supports for urban life. Consequently, drawing up a table of categories enabling us to understand the relative importance of each one must be based on comparative study – interrelating the cases to each other and their individual contexts, considering the references from national culture as a whole and from the Western cultural spectrum too.

[ Carlos Dias Coelho ]