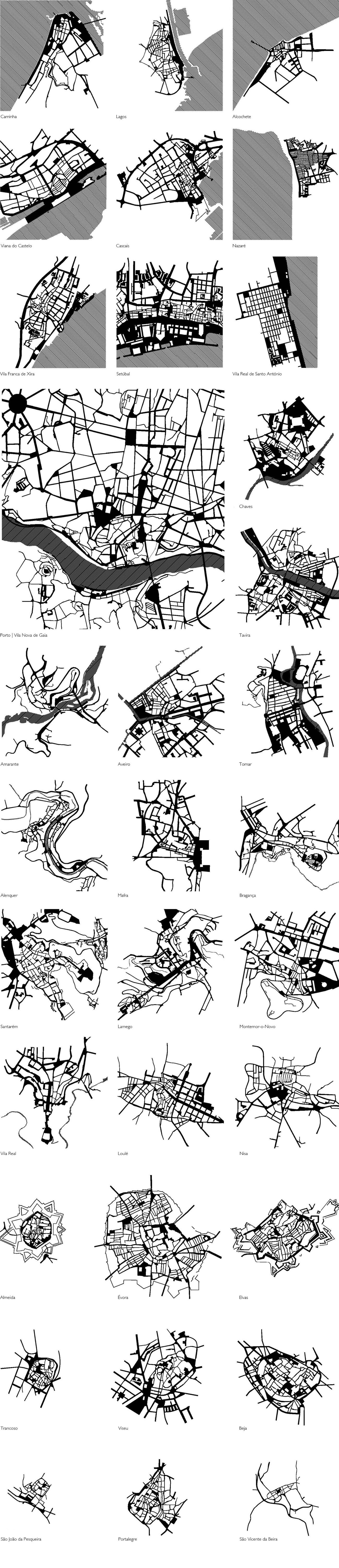

THE URBAN LAYOUT DIVERSITY

In terms of the various components that make up a city, the physical side has persevered alongside human activity and states the specific nature of its identity as time goes by. As a collective object, it can be seen as something that has been built and rebuilt on the same space, a single surface that mirrors the contributions left by each generation on the area.

In their complicated nature, cities comprise a wealth of features laid out with a public and private face. Thus, by focusing on the specificities of public spaces, we use the layout as an analytical tool, resulting from isolating the public component from the fabric and reducing it to a two-dimensional illustration. In this way, the urban layout is a concept that is based on interpreting the urban shape, revealing how it weathered the storms of time as the city evolved and recording the tensions between the two spatially distinct components.

By analysing the layout, we can understand the origins behind the spatial formation of the urban fabric’s public component. This analysis enables us to uncover phenomena, actions or factors that help explain each city’s formal specificities.

With an approach focused on the genetic diversity of city urban layouts, we can make out those that are pre-designed, as they follow a process of thought or a preconceived idea from compositional systems for public spaces. Some of these layouts date back to when cities were founded; others were designed with the aim of materializing the growth of existing nuclei. However, layouts produced through total or partial transformation of an existing fabric are also included in this class. This includes extensive urban regeneration projects or the local opening of new public spaces.

When urban layouts result from a process of organic sedimentation, the underlying motives for the human intervention that contributed to their formation are, on the one hand, for the square or road to develop independently, and on the other, for the plot, building and block to do the same. Much deliberation goes into positioning these features on the ground and this is what shapes growth or regeneration of urban features. In this manner, the layout stems from types of occupation themselves shaped by factors affecting the locus. Other unaccountable factors have their hand to play, as does the long time frame, in the formation process.

Interpreting the layout may also mean looking at a representative sample of the whole. These partial samples, which are generic pieces, are far removed from a global description of the urban entity. They ease our understanding of the facts involved in the layout’s formation in order to show the result of an urban configuration, from where we can uncover a model.

Analysing urban layouts can be seen as an opposite procedure to producing the urban shape: when we undertake an exercise of investigating and classifying urban layouts, we start breaking them down into their individual ingredients, allowing us to guess at the models from which they have evolved. [ Sérgio Fernandes ]